Active Witnessing: Guiding Kids of All Ages To Do the Right Thing

Active Witnessing: Guiding Kids of All Ages To Do the Right Thing

When our family (KM) recently moved, my children discovered that in each of their new schools’ peers were using racist, sexist, and homophobic remarks, something they had not previously experienced. My kids were woefully unprepared - and it turns out this is not unusual. When it comes to these types of remarks, which we believe is a form of bullying, the research supports that while kids know what they are seeing/hearing is wrong, they often lack the skills to respond effectively1. This personal experience, coupled with our knowledge of the research, means that we parents and educators must be better prepared to help our children and adolescents actively address racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, and other examples of prejudice and discrimination that arise when they socialize. If we don’t, BIPOC youth as well as those who identify as LGBTQIA2S+ or who have neurodiverse needs, will continue to experience the bulk of the pain and exclusion when these situations arise. However, white, cis-gendered, straight, neurotypical kids also are affected. When language and actions born of contempt and exclusion play out, if kids with privilege remain passive bystanders, they internalize subtle messages that those without the same privilege do not deserve equitable treatment. This can then place them on a path towards lifelong discriminatory practices. Therefore, as parents and educators we must become comfortable addressing these issues. This can begin with antiracist parenting and teaching children to understand the context and history to the words they use. But ultimately to promote values of equity, diversity, and inclusion while simultaneously maintaining strong social connections, all kids need to have a set of concrete skills to navigate these situations.

Shifting culture: Transforming the silent bystander into an active & ethical witness

There are well established educational programs designed to teach people to be active bystanders and step forward when they witness discrimination in action, and excellent articles written on this topic. However, if you don’t already have familiarity with such a program, we’d like to introduce you to the Anti-discrimination Response Training (A.R.T.) Program: An Active Witnessing Approach to Prejudice Reduction and Community Development. Dr. Ishiyama designed A.R.T. to help participants develop their “response-ability” or readiness to respond to racism. In addition, long time educator Angela Ma Brown has translated the wisdom of ART into classroom learning modules designed for students from K-12. Her program, “Break the Silence: The Power of Active Witnessing,” uses theatre and role-playing activities to guide students in this important work.

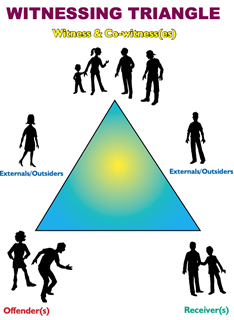

ART outlines 5 main parties involved when racist situations arise, which are: Self as witness- The observer; The co-witness/es- Surrounding observers; The offender- The person who engages in the discriminatory remarks or actions; The receiver- The person who receives the discriminatory remarks or actions; and Outside supporters- Others one can turn to for support.

ART outlines 5 main parties involved when racist situations arise, which are: Self as witness- The observer; The co-witness/es- Surrounding observers; The offender- The person who engages in the discriminatory remarks or actions; The receiver- The person who receives the discriminatory remarks or actions; and Outside supporters- Others one can turn to for support.

In addition to different parties there are also different levels of witnessing in response to discrimination, which are:

In addition to different parties there are also different levels of witnessing in response to discrimination, which are:

- “Dis-witnessing” involves the greatest amount of disengagement and avoidance, such as when a child sees something on the playground and simply ignores it.

- “Passive witnessing” involves silenced witnessing, which may include preparation for more active types of witnessing; this might be the stage where a child considers how to respond to the situation internally but lacks outward action.

- “Active witnessing” is any overt behavioral response to an event, including both immediate and delayed responses. For instance, a child might physically intervene or have a conversation about an event later with a parent or teacher.

- “Ethical witnessing with social action” involves taking that action to a social level in which the witness becomes an agent for societal and institutional change. For many adults, this is our own goal and the goal for the children we are raising. Examples include the development of a formal, institutionalized group or event - such as a school’s Gay-Straight Alliance or annual Black History Month parade - that provides an outlet for organizing more people in the fight for social justice

For obvious reasons we want to support parents and educators in working with their children and teens to be witnesses who support receivers, and in order to do so, to learn and rehearse active and ethical witnessing.

Getting Practical: The Do’s

When teaching active witnessing the aim is to have the child generate and practice a number of responses appropriate to them. For example, a child may be able to use an assertive interjection such as, “Stop!”, or describe their own emotion about the situation, “I’m surprised you think that.” Kids can be encouraged to call it what it is, “That was racist,” and express disagreement, “That’s not true,” or question the validity of the statement or overgeneralization “Everybody?” Other types of active witnessing include pointing out the hurtful nature of the statement, “Ouch!”, putting the offender on the spot, “Can you repeat that?”, and empathic confrontation, “It sounds like you’re mad.” When the child takes additional steps to support the receiver, “I’m here for you”, approaching a co-witness, “Did you hear that?”, and asking for help, “Please listen to what just happened”, this may even lead them to ethical witnessing by the inclusion of helpful others who can further assist in creating systemic change.

When children learn about the myriad of active witness options they can utilize, parents and educators may wish to encourage them to select options that correspond to their personality. For example, confident and outspoken youth may find calling out the offender’s behaviour comes naturally and easy to them, and kids who like to joke around may do well to diffuse the situation with humour. Alternatively, a quiet and more introverted kid may be better suited to go seek help and connect with the receiver afterwards where they can provide empathy and support in private. Once the child has selected a few examples, have them write these down on cue cards or store them on an electronic device for ease of use. Then encourage them to practice their planned responses. Knowing what they are going to do as an active witness before they need it is key. Keep in mind that these behavioural patterns don’t get established instantly, and it can take incredible courage to be an active witness when you are the only one stepping forward in a sea of passive witnesses. Celebrate your kids’ actions no matter how small and encourage their growth over time by reviewing together how the situation went and what they might do differently the next time they encounter a racist offender.

Getting Practical: The Don’ts

Not all active witnessing is created equally, however. It’s important to be careful that receivers aren’t placed at increased risk with active witness support. BIPOC kids are always at risk of being racialized, and they may fear that once their active witnesses have left and the incident has passed, that the offender may retaliate and continue. As a result, BIPOC kids may deflect the support they receive from active witnesses to protect themselves, which can confuse witnesses who lack a nuanced understanding of the precarious situation receivers may face. In addition, many kids in the middle and teen years simply wish to fit in, and any unnecessary attention is keenly avoided. BIPOC, LGBTQIA2S+, and neurodiverse kids are no different. When they are thrust into being a receiver, they may reject the attention it brings as this often serves to further “other” them which goes counter to fitting in. As a result, they may even downplay the impact of the incident, especially if the offender is a friend of theirs, which can be confusing for active witnesses. Encouraging children to consider ways to support receivers in ways that won’t draw attention can be a helpful way for them to take action while reducing further harm.

Kids should also know how to respond when their best efforts just don’t work. If the offender won’t back down or becomes more verbally or physically aggressive, kids should ask for help from a trusted peer or adult. And thoughtful attention should be given to BIPOC, LGBTQIA2S+, and neurodiverse kids who may be in a clear minority in their schools and should be connected with mentors, such as older students or staff whose identity aligns with theirs

It’s an imperfect journey we must all join

In an ideal situation the receiver will be grateful for the support active witnesses provide, and in many instances they are. However, as much as we may want the receiver to appreciate our child’s active witness efforts, their actions need to occur with no expectations of the receiver. BIPOC receivers don’t need to thank active witnesses, nor do they owe our children anything. If we are to even approach the prospect of dismantling racism, we need our children to engage in active witnessing because it is the right thing to do and not because it makes them feel good. This is hard for many adults to grasp, so give your kids support if they experience the sting of their actions going unappreciated or even rejected, and help them to understand why.

Like many aspects of parenting, teaching kids to be active witnesses does not require perfection. Kids and adults alike require practice in a safe and supportive place, such as at home or among close friends. We can teach our kids that advocating for justice is a lifelong endeavor that includes mistakes and missteps. We can also consider each situation a learning opportunity to hone skills that will improve our response for the next time a situation arises.

References:

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1053992.pdf

-

Adapted from Angela Brown, M.Ed. & F. Ishu Ishiyama, Ph.D (2009). Break the Silence:

The Power of Active Witnessing. 80 Intermediate Curriculum Document. Vancouver

Board of Education. - Microsoft Word - Ishiyama 2014 ART Program introduction 7-page booklet (v2014).doc (wordpress.com)

And a special thanks to Sharyn Carroll and Deblekha Guin for their time and thoughtfulness in reviewing these documents.