Minute-by-Minute: Changing the Way we Measure Anxiety

Minute-by-Minute: Changing the Way we Measure Anxiety

Anxiety takes many shapes. Some experience physiological anxiety (e.g., racing heart, sweaty palms), some fear specific spaces, and others are plagued by self-doubt and worry. The anxiety may be unrelenting or may wax and wane over the course of months or years. Moment-to-moment, month-to-month, our symptoms fluctuate greatly depending on the situation we are in, the state of the world (for example, a global pandemic), and the interactions we have with others, to name only a few. There are countless combinations and fluctuations of symptoms and severity.

The good news is, we have highly efficacious treatments for anxiety disorders, backed by decades of research (Cuijpers et al., 2016). The not-so-good news is, it is often common for a patient to not respond to treatment, or, after achieving reduction of symptoms, to relapse back into debilitating anxiety. The real-not-so-good news, we have made relatively little progress in recent decades in improving our treatments to address these shortcomings. The critical question facing researchers is: how can we learn more about anxiety and anxiety disorders in order to better help those suffering from them?

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

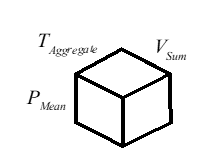

Part of the answer lies in how we measure anxiety in our clinical research. We find it helpful to think about this issue in the framework of Cattell’s data cube, as illustrated in Figure 1 (Cattell, 1988). In this cube, we have three planes: persons, variables, and time. Traditional anxiety treatment research typically entails gathering data about a given variable (e.g., worry) collapsed over an extended period of time (e.g., the past month). Typically, researchers then add a number of time-collapsed variables together to get a total disorder severity score, which gets collapsed further across a large number of participants. In other words, we take all of the information in Cattell’s data cube, and we condense it into a single parameter (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

While we’ve gotten far in psychological science using mean scores, there are significant limitations to this method. For example, it is difficult to reflect on an entire month and aggregate weeks of experience into a single self-reported score. We have little idea how participants make these judgements and, as a result, it is unclear precisely what these variables collapsed over time represent. More fundamentally, we lose all the intricacies and individual differences that characterize the reality of having anxiety. In other words, we lose much of the rich information that exists within the Cattell Data Cube.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a tool that can help us gather that intricate, person-specific data about anxiety. EMA involves repeatedly gathering data about an individual in real-time as they go about their daily life, through use of written diaries, mobile applications, or wristband devices that passively capture psychophysiological symptoms. This methodology allows us to collect data about a single participant’s specific symptoms at a single point in time.

For example, at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), we use a mobile application and wristband device to capture self-report and psychophysiological symptoms of panic disorder prior to and following cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. The mobile application sends participants surveys five times a day, every day, for two-week periods pre- and post- treatment. By doing so, this methodology allows us to better understand the individual, lived experiences of anxiety for specific people throughout treatment.

EMA allows us to collect data that we typically struggle to capture. By taking brief, self-reported assessments of symptoms (~1-2 minutes to complete) and passive monitoring from the participant multiple times a day, we can capture the ups-and-downs of living with anxiety for one specific person. We can track which specific symptoms of anxiety change, when they change, as well as the interrelationships between symptoms throughout a day (e.g., how avoiding looking at your bank statement may lead you to feel more worried about your finances, which may lead you to avoid checking the statement even more). The goal of such research is to better understand how an intervention works, for each specific person, so we can tailor treatment that leads to better outcomes. At MGH, we hope that our rich EMA data will allow us to create a highly individualized, precise CBT intervention for panic disorder that boasts these promising outcomes.

EMA allows us a glimpse into the real-world experience of living with anxiety disorders. Although more cumbersome than filling out a survey once a week, we believe that the benefits vastly outweigh the cost. Indeed, we believe this tool will ultimately help us better ensure that the interventions we offer to patients have the maximal benefit possible to alleviate the daily toll of anxiety.

Figures:

Figure 1. The Cattell Data Cube, illustrating the three planes we typically assess in anxiety research: persons over variables over time.

Figure 2. This cube exemplifies all of the intricacies of anxiety that we traditionally collapse across when engaging in anxiety treatment research.

References

Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders

Cattell, R. B. (1988). The data box. In Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (pp. 69-130). Springer, Boston, MA.

Cuijpers, P., Gentili, C., Banos, R. M., Garcia-Campayo, J., Botella, C., & Cristea, I. A. (2016). Relative effects of cognitive and behavioral therapies on generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder and panic disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 79-89.